I approach Mairi’s studio and she opens a heavy metal door to a surprising indoor garden and we chuckle at the fact that she’s wearing a cap that says ‘steups.’ Small traces of light seep through the pathway and there is a distant sound of other artists at work. This is a gentle reminder that we’re both in the right place.

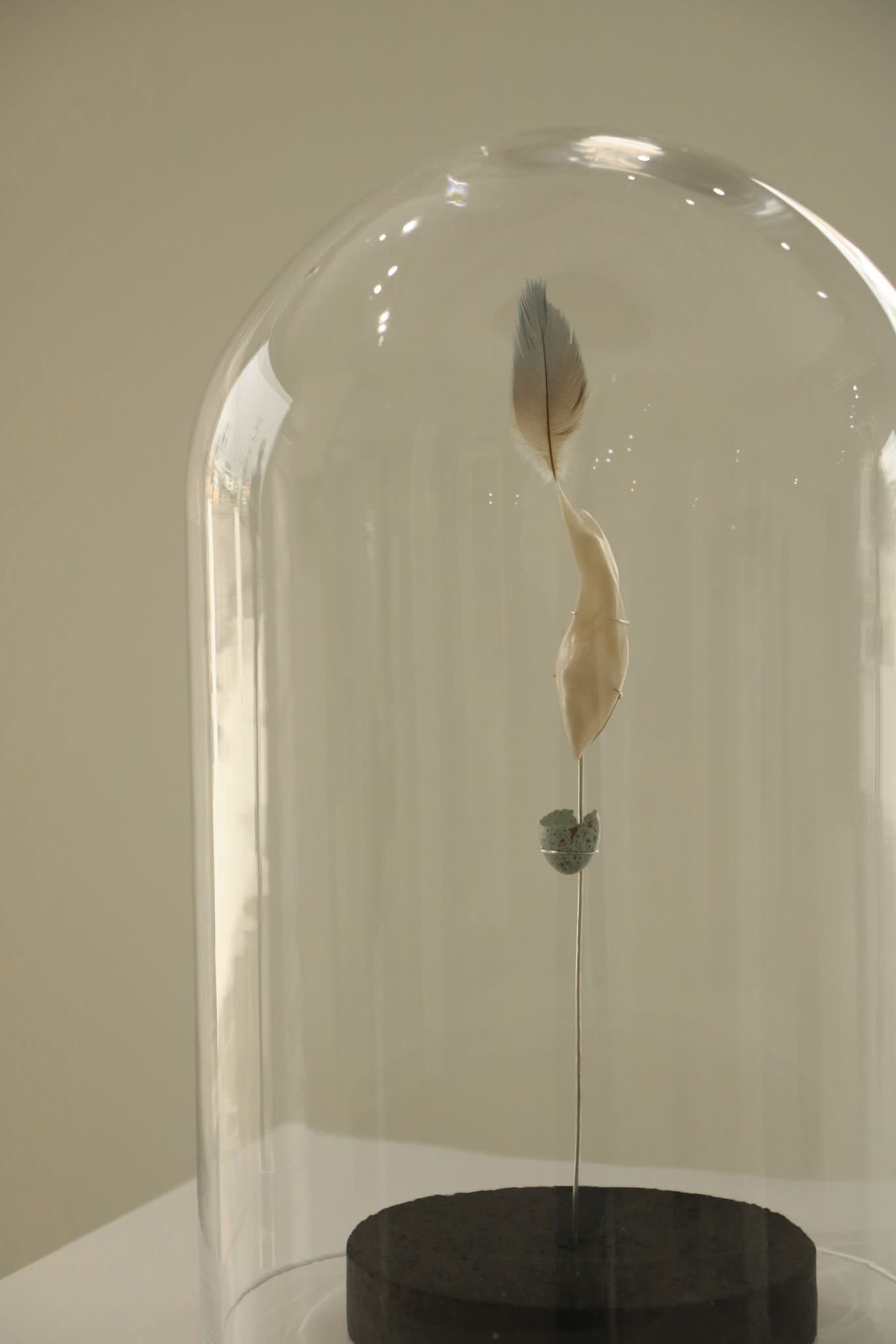

I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing Mairi for a digital platform called Designer Island in 2017, making this a full circle moment, as I bear witness to her journey as an artist through the years. I look at the pieces delicately laid out on a table– awaiting their visitor– and I’m enamoured by the approach she’s taken since her debut. It is said that in 1000 BC, the earliest inhabitants of the Caribbean islands, more notably Trinidad, were named ‘Ciboney’ and they cultivated a livelihood for themselves by means of hunting and gathering. It is no coincidence, therefore, that modern and contemporary Caribbean artists often use their inborn gift to seek and collect as part of their creative process; deriving notions of land, place, and time. It is clear to me that Mairi’s Ciboney tick is not only prevalent in her practice, but also in her partnership with nature’s timing. Wood, feathers, wings, eggs, shells sit before us, telling me that there was a life before this form. She walks me through the intricate process in scouring these finds, while setting a timer for the resin of a piece-in-progress to dry. Her studio is an orchestra, with numerous characters who hold space in the performance of her work. I smile knowing I got the first seat.

To Millar, each piece is the result of a “collaboration with chance,” thereby nodding to the fact that nature’s supply offers the artist both limitations and opportunities to see things differently. Despite the fact that these objects are recognisable to everyday life, encountering them at their after-life creates another realised energetic matter. What is left from a life lived? The objects we leave behind are markers of time, where-in the case of Mairi’s inquiry, are Signs Of Life. Yes, life. The gusto and terror of the one thing we have inadvertently subscribed to. It plasters her wall in the form of a poem by Jaime Sabines, “someone spoke to me every day of my life | in my ear, gently, slowly. They said to me: live, live, live! It was death.” Her work traces the delicacy of breath and the power in trying again; it’s a resuscitation of the ugliness and beauty in our everyday decay. I find myself revering the relics as she, almost prosaically, speaks of their equal power in the wider display of the exhibition. According to Millar, “the smallest detail could completely reinterpret the meaning behind each object, so even understanding the space they inhabit is a high priority for me,” hence, everything is considered– something I’ve always admired about her. She accounts for the interactive dance we as viewers are permitted when engaging with her craft, so that, too, the objects dance with us: letting us know that it’s alright, and we, like them, will transition into the new life they’ve taken on.

Together, Mairi and I leave her studio and joke about the descent into nightfall, and I subconsciously consider my own inquisition of darkness. There’s something to be said about the way we squirm at the raw and the rotting that happens in nature and in life, to which Mairi gives power to. And so I urge you, reader, to walk into Millar’s exhibition with all your imperfections and flayed souls, and look– I mean really look– at nature’s truth before you. Live, live, live.